In his dissenting remarks on the 1987 U.S. Supreme Court case McCleskey v. Kemp, Justice William Brennan pronounced that “those whom we would banish from society or from the human community itself often speak in too faint a voice to be heard above society’s demand for punishment. It is the particular role of courts to hear those voices.” He wrote these words to defend Warren McCleskey, a black man convicted of murder in Georgia who had argued that capital punishment’s documented racial bias violated his constitutional rights. Though with good intentions, Brennan was wrong to indict these voices as too quiet – that the courts alone could amplify them. Incarcerated Americans from the country’s first penal experiments to today’s facilities frequently bear testimony beyond the limits of legal procedure. Through letters, magazines, sub rosa manifestos, and memoirs they appeal their sentences, contest the conditions of confinement, seek solidarity with social movements, and deliberate over what punishment means for political democracy.

As a scholar of American political thought, law, and literature, I recover and reconstruct the political and legal thinking of incarcerated figures who testify beyond the judicial process. I focus particularly on historical figures looking to reform or reduce the role of prisons in society. With an interdisciplinary approach, I combine textual analysis of popular and archival writings with historical analysis of legal and institutional developments in American penal policy. As Robert Cover wrote, “no set of legal institutions or prescriptions exist apart from the narratives that locate it and give it meaning.” My work recovers imprisoned voices as offering narratives that counter those of the procedures and institutions that incarcerate them. Reconstructing their ideas within their own historical and legal contexts illuminates key developments in U.S. thinking on prisons as well as enduring tensions in our contemporary approaches to punishment.

This research has resulted in a number of published articles and a new book project, building from my first book and earlier work on life writing and American democracy.

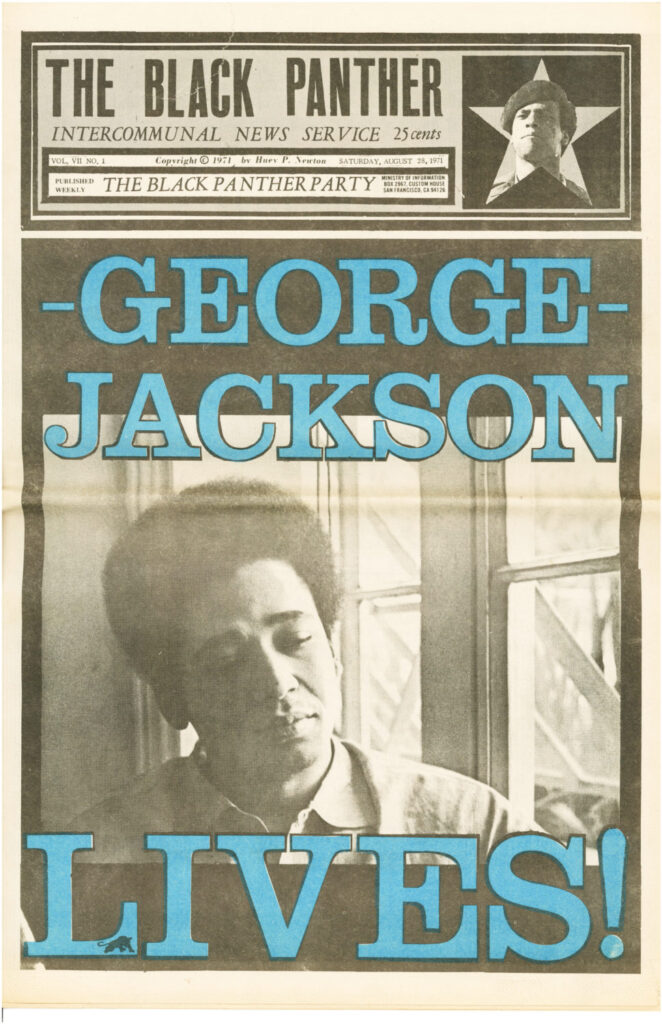

George Jackson Lives!

Law, Liberation, and the Ends of Incarceration

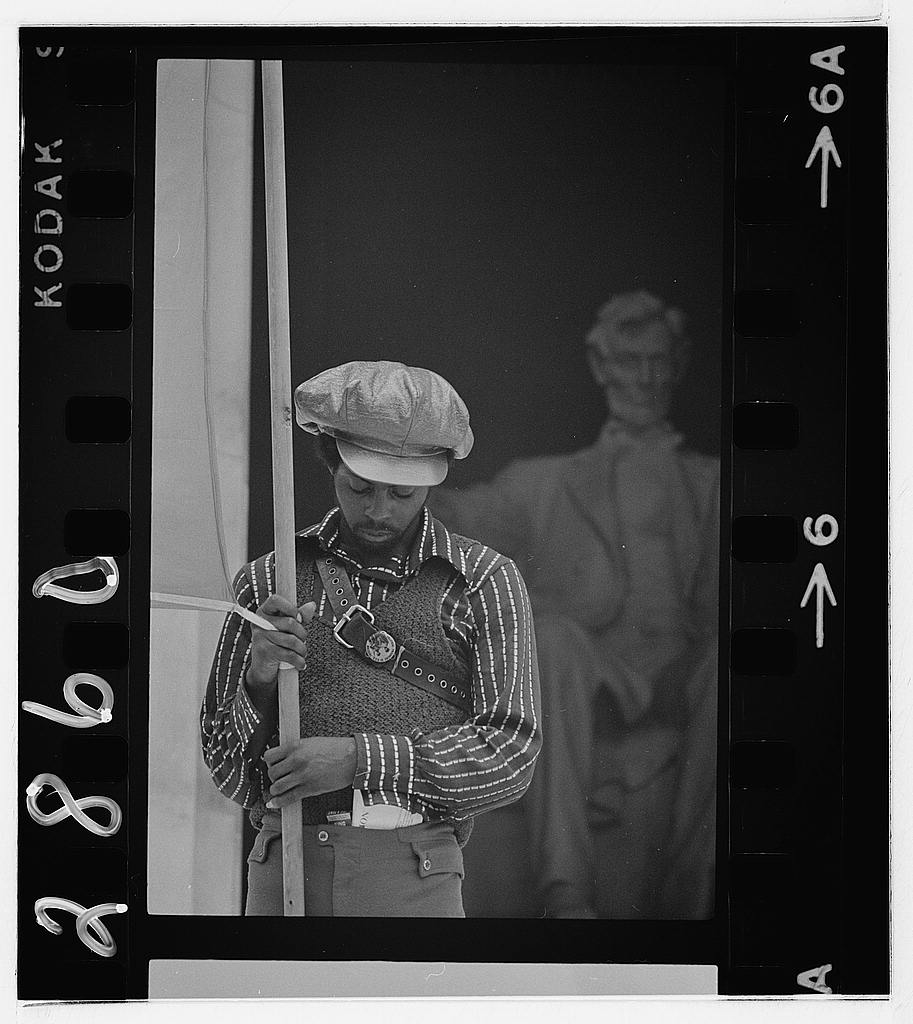

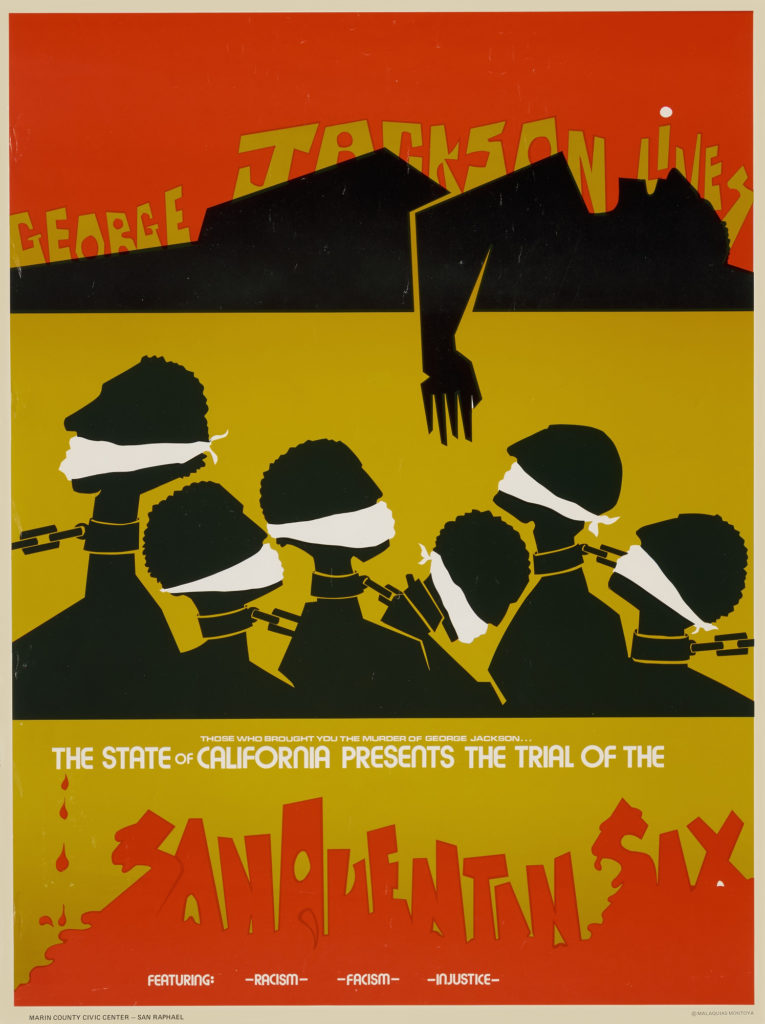

In this new book project I recover and reconstruct the writings of influential and incarcerated activist George Jackson. Jackson entered prison at the age of eighteen in 1960 with an indeterminate sentence for petty theft: over the next eleven years he moved between California facilities, engaged in strikes, self-defense and political education among prisoners, and joined the Black Panther Party. In January of 1970, Jackson and two other men were accused of murdering a guard, an accusation that inspired demonstrations and violence behind bars, political and legal efforts to exonerate the “Soledad Brothers” beyond, and a number of authored books and essays by Jackson before he was killed during an alleged escape attempt from prison. A controversial figure, Jackson was nonetheless lionized by many following his death and inspired numerous activist groups in and out of correctional facilities.

In an article for New Political Science (2022) I sketched Jackson’s views of violence through his analysis of what he called a “captive society” and advocacy for revolutionary activity like the “perfect disorder” that would disrupt law and order politics.

George Jackson Lives! expands my study of Jackson’s writings and contexts. I propose Jackson’s life and legacy as a prism through which to understand a variety of legal, institutional, and political developments during the twentieth century: e.g. the use of “bibliotherapy” in California prisons, indeterminate sentencing and its decline, the rise of the Black Panther Party, and prison politics into the twenty-first century.

After an initial chapter that traces the institutional and legal history of California’s San Quentin and Soledad prisons, the following chapters reconstruct areas of Jackson’s thought: his identification as a political prisoner, writings on love and kinship, violence, and hero worship.

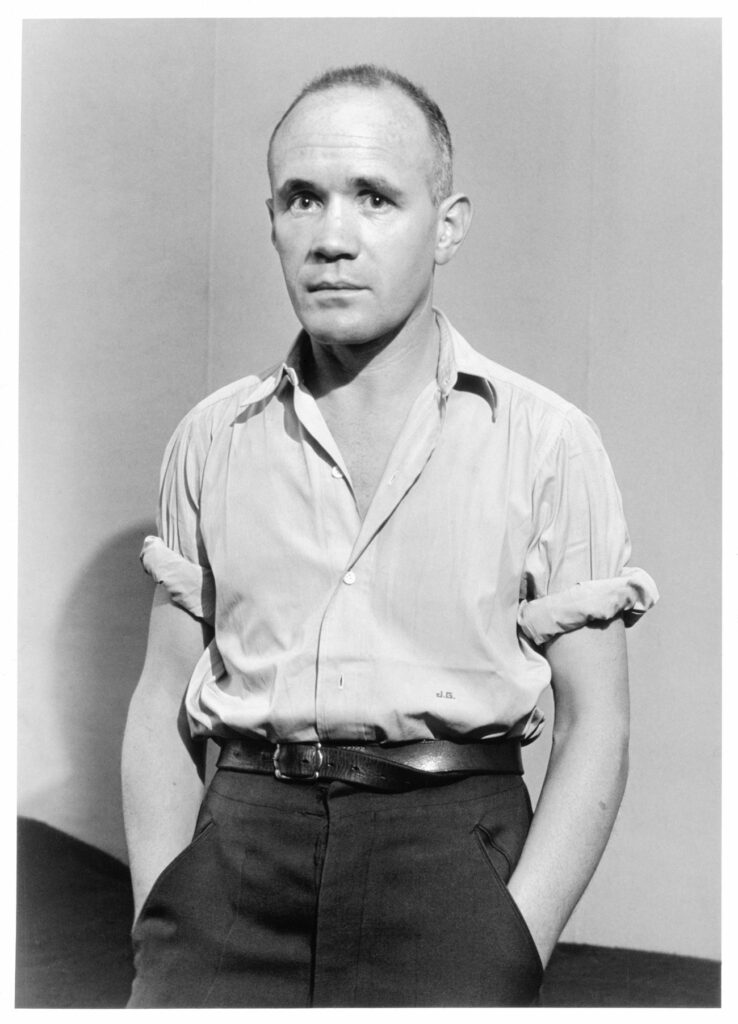

As a fellow for UW-Milwaukee’s Center for 21st Century Studies last year, I produced original research on the French activist and playwright Jean Genet, who lectured throughout the U.S. with members of the Black Panther Party and advocated for Jackson, inspired by his own experiences incarcerated in France.

George Jackson Lives! will reconstruct Jackson through his writings, the institutions he inhabited, and relationships like these, treating penal thought as a comparative, complex construction of people, places, and policy.