Across universities I’ve taught a variety of courses in public law, political theory, criminal justice, and literature, at both the undergraduate and graduate levels.

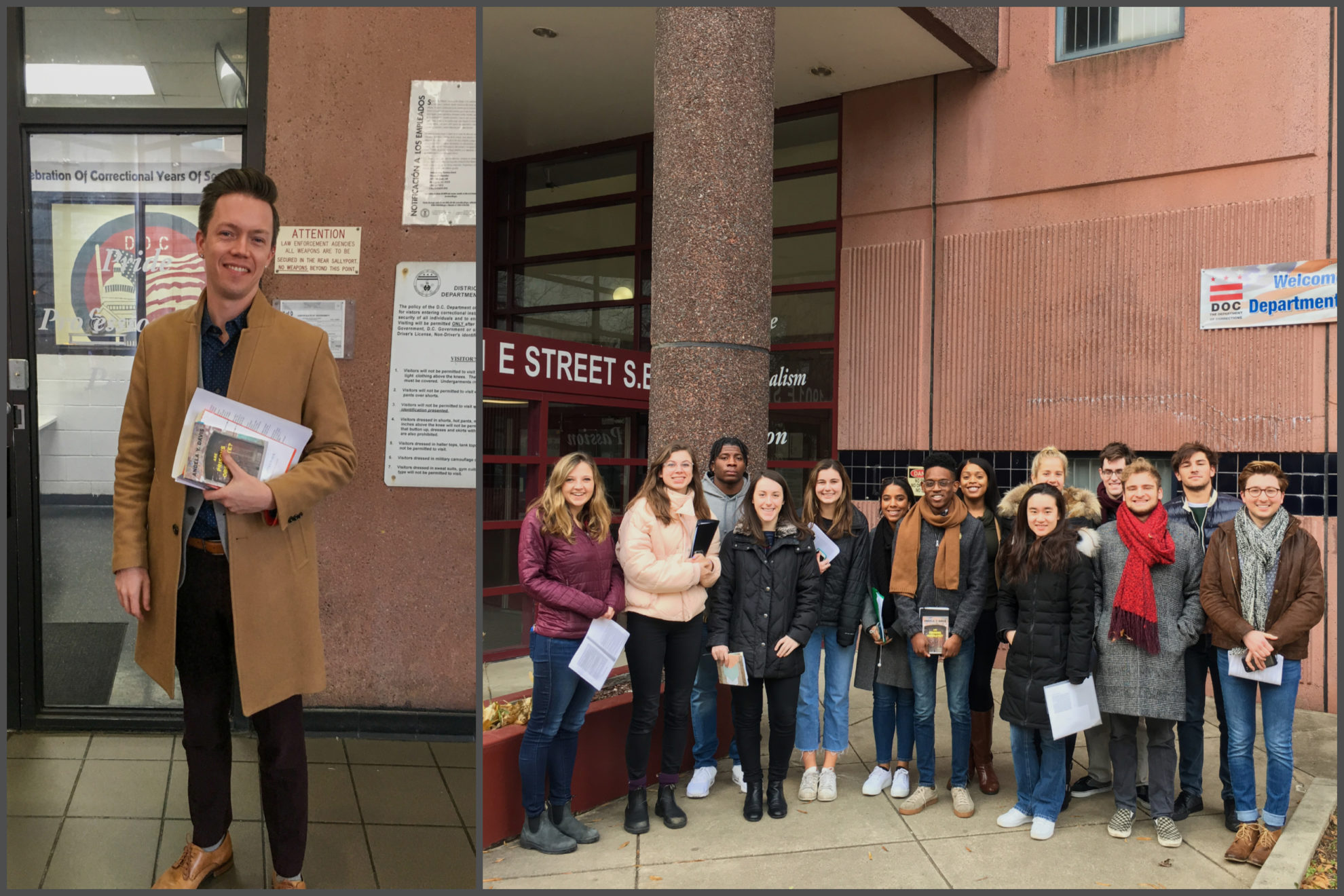

I’m particularly committed to teaching and learning in correctional facilities through prison education or inside-outside programs. You can read a bit about one of my experiences here.

Below are a few of my favorite courses:

“Law and Society”

A typical depiction of law brings to mind any number of images: lady justice with her blindfold and scales, legislators debating procedure within the capitol while protestors and police clash outside, attorneys and judges locked in heated dispute over rights and rules.

In this course we will go beyond these images, to envision law as a social phenomenon that shapes our own lives every day. We will begin by considering how others across history have defined law: as a source of morality or justice, a reflection of economic development, an institution among others that regulates human life while relegating some lives as inferior. From there we will examine the many ways that law informs our reality: how it impacts our thinking, our identities, our efforts to change our conditions. We will study how today we inhabit multiple legal frames, how and why the law often fails, and what hope we might find in the law when pushing for justice. We will adopt a number of disciplinary perspectives ranging from philosophy to sociology and political science, covering topics in the U.S. and across the globe on race, gender, sexuality, surveillance, violence, immigration, policing, prisons, food trucks and more.

“Prisons and Punishment”

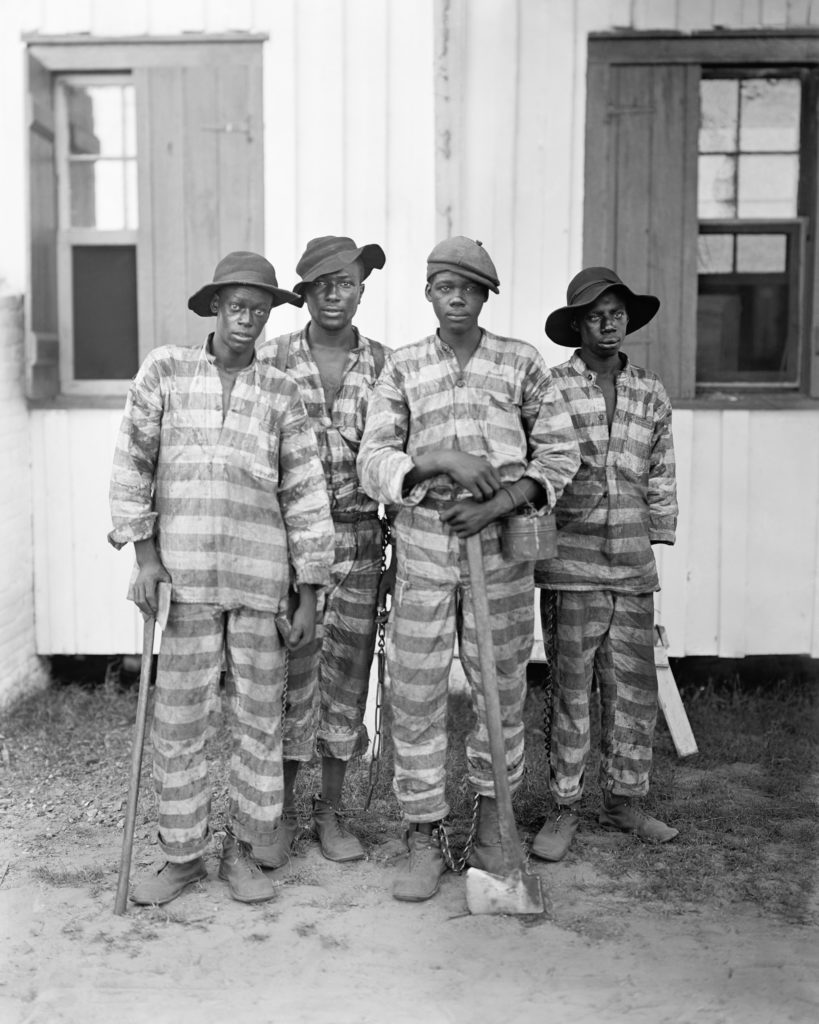

The novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky once remarked that “the degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” What then could we say of mass imprisonment in the United States, a nation with five percent of the world’s population yet twenty-five percent of its prisoners? How should we understand American democracy if one in twenty-three adults are under some form of state supervision, if one in ten children have had a parent incarcerated, or if one in three black men born today will enter prison at some point?

In this seminar we will study the ethical and political challenges of crime and punishment in the United States, looking at the ideas, institutions and history of American incarceration. We will begin by looking at the philosophy and sociology of freedom and punishment before working through a series of case issues in incarceration that will take us from society to the jail to the prison and back again. Students can expect to read broadly from political science and theory, philosophy, history, sociology, and from the testimonies of those living within, working for, or acting against the carceral state.

Find the syllabus here.

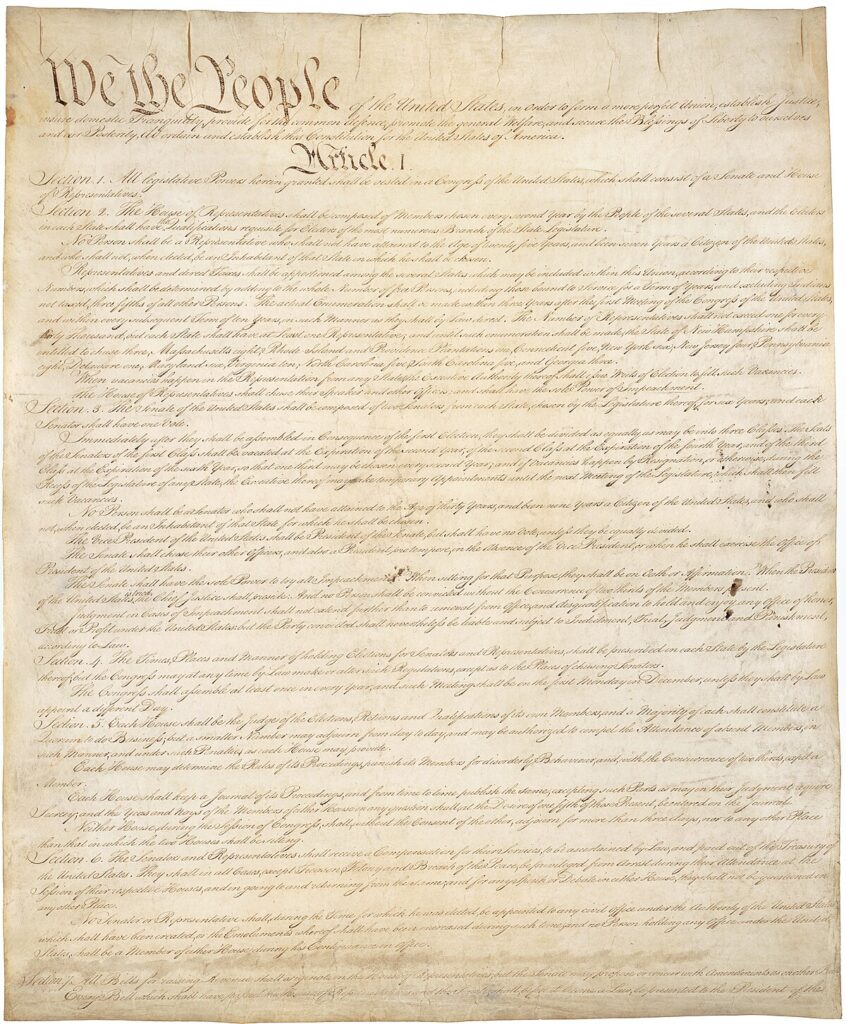

“Constitutional Law”

In 1919, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. echoed the framers in calling the U.S. Constitution an “experiment, as all life is an experiment.”

But how successful of an experiment has it been? In this course we will engage this question by studying the foundations of American constitutionalism in theory and practice, with particular attention to the Bill of Rights and Amendments. We will study key court cases as well as the political contexts and ideas surrounding them: though we will often focus on the Supreme Court, our goal will be to evaluate the Constitution as a popular, democratic document. Our readings will take us through issues of religious exercise and establishment, guns, privacy, gay marriage, free speech and the press, democratic participation, equality of race, gender, sexuality, and class, and criminal justice.

“American Political Thought”

“O, let America be America again,” Langston Hughes wrote: “The land that never has been yet – and yet must be – the land where every man is free.” Throughout the history of the United States, many, like Hughes, have described its founding ideas as inspirational yet unfulfilled. But what are these political ideas, this American “dream deferred”?

In this course we will survey the intellectual history of American political ideas from their English roots to the mid-twentieth century. Along the way we will critically examine abstract ideas such as freedom, equality, representation, labor, rights, and citizenship as they develop in the United States alongside histories of colonization, slavery, industrialization, immigration, war, and so on. Students will engage with these developments through a wide variety of primary sources: through pamphlets, declarations, speeches, memoirs, novels, debates, treatises, and court decisions. From these readings we will analyze American political thought as developed not simply by politicians and philosophers but by those on the margins as well.

Find the syllabus here.

“Political Theory”

Hannah Arendt famously described the “revolutionary spirit” of our modern world as “the eagerness to liberate and to build a new house where freedom can dwell.” But liberate from what and how? And what do we mean by freedom?

In this course we will engage questions like these through the study of political theory: the longstanding human effort to understand political life as it is and to advocate for what political life could be. We will study the writings of major and minor political thinkers and movements across history from antiquity to the modern era, with a particular focus on revolutions like those of the United States, France, Haiti, Russia, and China, industrial and intellectual revolutions, and more. By tracing the development of ideas like freedom, government, equality, violence, identity, race, class, and gender, we will better understand their history and relevance for our own political lives and revolutionary era.

“Politics and Literature”

To know justice, James Baldwin wrote, requires we listen not to the judge but the “testimony” of those “who need the law’s protection most.” What is justice, and how should we define it?

In this course we will examine key issues of political and moral justice as explored not through law or philosophy, but literature: in novels, short stories, memoirs, letters, drama, science fiction, and so on. These works will offer us diverse arguments about justice to master and evaluate, arguments that may frame justice as a hierarchical system of governance, as utopian, as an ethical way of life, as meritocratic individualism, as a form of individual resistance or revenge, as reconciliation, and more. Along the way, we will compare these literary approaches to justice with those found in political theory, philosophy, and public policy.

Find the syllabus here.

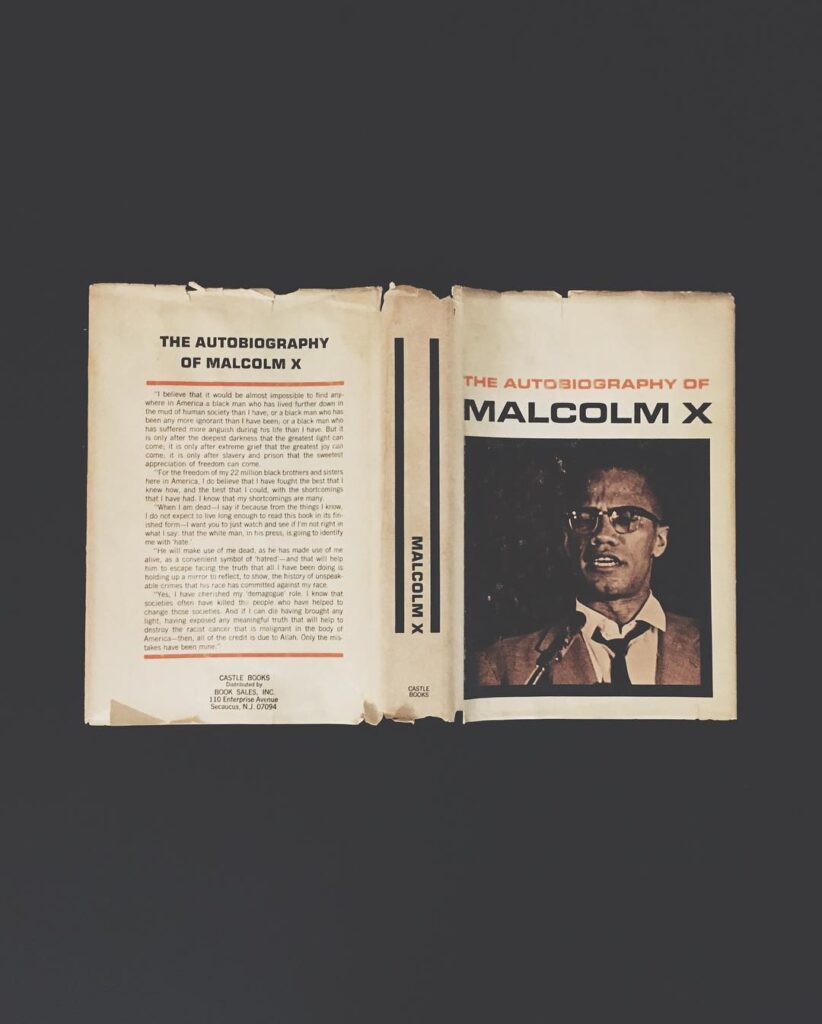

“Autobiography and American Democracy”

Since at least The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, American thinkers have written their life stories for various political purposes: to outline an ethical way of political life, to resist authority or injustice, to insist on the author’s place among the people, and so on.

This course surveys those political actors who have drawn on autobiography to champion or critique American democracy. We will investigate how actors use the genre to wrestle with topics such as the relevance of morality for citizenship, whether participants should draw on experience in political debate, how democracy should respond to histories of injustice, and how citizenship should best reflect a diverse public. We will read authors such as Benjamin Franklin, Black Hawk, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, Henry David Thoreau, Booker T. Washington, Henry Adams, Emma Goldman, Whittaker Chambers, and Malcolm X, as well as engage with recent examples of personal narrative in immigration, sexual identity, and presidential politics.

Find the syllabus here.